Celebrating Pioneering Black Industrial Designers

“Where are the Black Designers?” This Black History Month, as we continue to ask this recurring question, I take the opportunity to celebrate three pioneering Black Industrial Designers who have had an immense impact on the profession, and my career, in different ways.

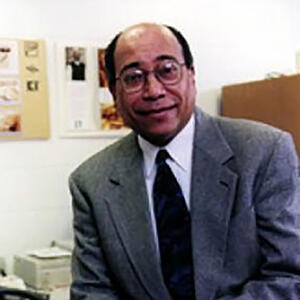

Dr. Noel Mayo (December 30, 1937 - )

Owner of the first Black industrial design firm in the United States

If you have ever seen a Lutron dimmer, Dr. Noel Mayo designed it. In fact, his influence is seen within all of their products, down to the design of their buildings, and even the personal homes of the company’s owners. Lutron is number one in innovation, quality, and sales of dimmer solutions and is one of the most successful companies in the world, in part, because of Dr. Mayo’s design contributions. For more than 50 years, he has been and continues to be their lead design consultant with over 2,000 Lutron design and utility patents.

Graduating in the industrial design class of 1960 from the University of the Arts (formerly the Philadelphia College of Art), Dr. Mayo was the school’s first Black graduate. In an inconceivable set of circumstances, he started his professional practice as a junior in college working part time for a local design team that included the head of the industrial design department and a faculty member. He was thrust into leadership when two partners suddenly went to Europe and left him in charge of the office. He worked independently at first, before hiring classmates to assist in completing the work, which was done successfully and profitably. After graduation from university, he took over the business in 1964. This story is wonderfully captured in a History Makers video interview.

As a holistic design thinker, Dr. Mayo has led Noel Mayo and Associates, Inc. for nearly 60 years, producing successful industrial, graphic, and interior design work for national and international clients, including NASA, IBM, the U.S. Department of Commerce and Agriculture, Black and Decker, the Museum of American Jewish History, and the Philadelphia International Airport. In 1978, he accepted a position as chairman of the Industrial Design Department at the University of the Arts and simultaneously became the first Black faculty to head an industrial design department nationwide. Although the position was officially part time, within 11 years, he grew the department to be the third-largest in the college and grew its reputation as a nationally recognized, well-respected program.

In 1989, Dr. Mayo was named professor and the Ohio Eminent Scholar in Art and Design Technology at The Ohio State University, a governor-appointed position. In addition to teaching across the curriculum of the Department of Design, one of his key initiatives as Eminent Scholar was the creation of a Center for Diversity in Design where he dedicated his efforts, and those of graduate students, to identify designers of color, collect examples of their work, construct informational panels, and celebrate them by showcasing their work in his center and through a traveling exhibition.

Dr. Mayo has been instrumental in establishing various mentorship programs and connections for minorities to attract them to design and support them in the field. From his first appointment at the University of the Arts, through his recent retirement as an Eminent Scholar, he led dual full-time careers as an educator and practitioner. He now focuses full time as a practitioner.

On a personal note, 26 years after Dr. Mayo graduated from the University of the Arts, I graduated from the same industrial design program in 1986. While several other Black students enrolled over those years, he shared with me that I was only the second Black student to graduate. Yes, he was my teacher. Almost a decade later, I was successfully working in the industry when he persuaded me to step back from professional practice and become a master’s student under his leadership at The Ohio State University. I accepted his invitation which, once again, opened my life to new possibilities and a path that would later lead to Carnegie Mellon University. Dr. Mayo continues to be a lifelong mentor and a dear friend.

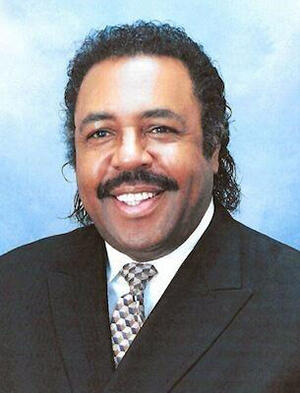

George L. Horton (June 16, 1939 - October 7, 2020)

Owner of the Second Black industrial design firm in the United States

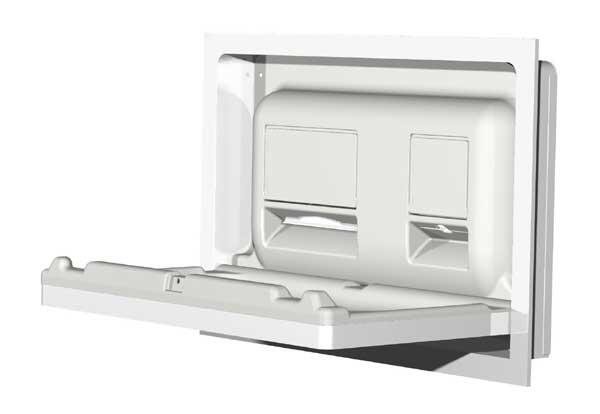

If you have used an American Standard porcelain bathroom fixture, have been served a formal meal on Corning Pyroceram dinnerware, or have used a diaper changing station for your infant, chances are that it was designed by George L. Horton. Horton, a 1961 graduate of the Rhode Island School of Design, worked for Corning Glass Works soon after graduation. In 1969, he joined Samuel J. Mann Associates industrial design firm located in Englewood, New Jersey. In 1973, he purchased the firm and expanded its capabilities by developing a portfolio that included medical instrumentation, exhibit and retail showroom design, and graphic communication services. The shift earned the firm multiple design and engineering awards over his 60 years of practice. He even designed caskets, igniting new enthusiasm in a closed industry, and later became a partner in the company.

Dr. Noel Mayo and George Horton knew each other. And while neither could recall how they first met, there was mutual admiration. Neither was aware of any other Black-owned industrial design firms and years later, they learned they were the first and second, respectively. While their professional paths never crossed, they had one common connection: me. In 1986, having graduated second in my class at the University of the Arts, I struggled to find employment when others seemed not to. Dr. Mayo made a phone call to Horton, told Horton about me, and endorsed me personally and professionally. Horton invited me to New Jersey for an interview and hired me the same day. It began my career.

When I joined Mann-Horton and Associates (MH&A), as it was named then, it was a small but diverse and quite successful design firm. The largest client at the time was Technicon Instruments Corporation, a then leading manufacturer of scientific instruments for the automated analysis of blood, serum, foods, drugs, water pollutants, and other products for testing laboratories and doctor’s offices. For several years, MH&A was the industrial design firm exclusively serving Technicon’s needs. On day one, I found myself in the deep end of the pool. It became clear that in school, I had learned well about design and acquired strong skills, however, George Horton taught me how to design.

Professionally, Horton taught and pushed me with the old-school tough love as a mentor training a protégé. My first assignment was to generate a range of new forms for a countertop diagnostic instrument. Having proudly pinned to the wall what I thought were strong, well-drawn ideas - of course, I wanted to make a good impression - his critique was unexpected. “These are good, but I can do these. I need you to blow my mind!” The designs he had no interest in, he yanked off the wall and let them fall on the floor. He ripped details from drawings that he was curious about, and pinned them to others for further exploration. Others, he marked up with a pencil. Although a bit stunned, I got the message. Over the next four years working for Horton, I contributed to the design of numerous industry, consumer, and retail solutions.

The core of my professional practice and approach to design and business was instilled by George Horton. He taught me how, as Black designers (he and I were the only Black designers in the office), we needed to function in the White business world. From the day I started, he taught me lessons about suppressing much of our ethnic culture during business hours. Matching the well-established corporate dress code was now obvious; Dr. Mayo had prepared all his students with this knowledge. However, modifying my speaking voice to sound more neutral was not as obvious and came from listening to Horton practice his to provide at least a chance for new business when he made solicitation phone calls. Suppressing ego often meant not acknowledging that he was the company owner, a common practice for Black business owners. It meant having White associates accompany him on sales calls to put potential clients at ease in thinking that a White man would be leading, or closely involved, with the service. As a small office, I had the opportunity to learn the business through engagement in business development and client relations, and operations and office management activities. I can still hear his chuckle and occasional facetious question: “They didn’t teach you that in school, did they?” I was now at George Horton University, a continued education that would prepare me well for the professional journeys he would encourage and inspire me to take.

Horton deeply loved design but found great joy in the business of design. As a result, he was decidedly not visible in design organizations, and he had little recognition in these circles. Instead, he chose to promote the value of design through leadership and service on the boards of various business organizations, through the occasional university lecture, and through youth mentorship. We remained extremely close, and he referred to me as his son. Sadly, Horton became ill and died peacefully in October 2020, days after interacting with senior design students at Carnegie Mellon University. It was his last joyful moment.

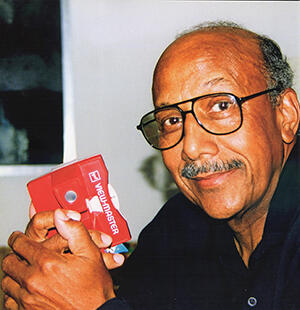

Charles “Chuck” Harrison (September 23, 1931 — November 29, 2018)

The first Black industrial designer to be hired by and lead the design group of the Sears corporation

It is very likely that you, or someone in your family, have used a product that was designed or influenced by Chuck Harrison. From furniture, appliances, and lawn equipment, Harrison designed more than 750 products for the Sears corporation - the Walmart of its time with a talented in-house design department - and over 32 years rose to become the first Black person to lead its entire design group.

Harrison was well-prepared for the Sears opportunity. His formal design education began at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago where he graduated in 1954 as the first Black person in the country to receive a degree in industrial design. He was immediately drafted into the U.S. Army for two years, then returned to Chicago in 1956 to attend the Illinois Institute of Technology where he completed his Master’s in Art Education. Yet, he struggled to break into professional practice due to racial issues in America. While his classmates were generally supportive, even identifying the opportunity at Sears, they were ahead of many in the industry in this regard.

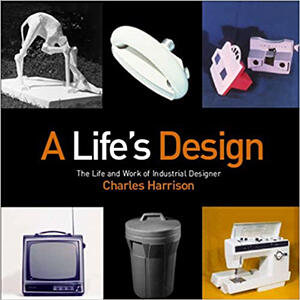

Harrison’s initial encounter with Sears in 1956, in response to a job opening, was met with rejection. While the design manager liked him and his work, there were policies of the corporation not to hire Black candidates. However, he made such an impression that the design manager provided him freelance work, which he did for Sears and others around Chicago until making a name for himself. Harrison then worked for a couple of established design offices in Chicago. It was at Bob Podall’s office where he redesigned the now-iconic GAF View-Master. In 1961, Sears called back. They could now hire him, which they did, and he began an extraordinary design career with the corporation. The late Victor Margolin, Professor of Design History at the University of Illinois, Chicago, wrote in his foreword to Harrison’s autobiography “A Life’s Design, the life and work of industrial designer Charles Harrison”:

“Some designers are known for the creation of two or three chairs or even a single chair, while Chuck worked on several thousand products that ranged widely from baby cribs and barber chairs to hearing aids, television sets, and tractors … Chuck is a true pioneer, not only because he broke the color barrier at a large American corporation but because he designed so many of the products [about 750 that reached the marketplace] that became and still remain part of the daily lives of millions of people.”

In Harrison’s retirement from Sears, he focused on teaching, inspiring, and guiding students, especially minority students, to find their successful pathways in design.

Having learned about Harrison, and being inspired by the highlights I had heard about his life, I needed to meet him personally. So, in the early 2000s, I called him up, introduced myself, and said I was heading to Chicago and would love to meet him. He was gracious and accommodating, and we met at his home over tea. We talked about his story, part of which was represented by original artifacts in his home that he had designed, and we talked about his book that was in production at that time. I left enriched and grateful to be connected to such an important figure in design. For more, see Charles Harrison’s interview with History Makers.

What if the connections could have been made sooner?

Dr. Noel Mayo and Charles “Chuck” Harrison, two Black pioneers of industrial design, didn’t know of each other and only met for the first time in the mid-90s. But they had several occasions to get to know each other thereafter. It was a beautiful thing. In 2006, I had the distinct pleasure of celebrating both uniquely. At that time, I was the first Black board member and officer in the history of the Industrial Designers Society of America (IDSA); I was serving as the Executive Vice President, having risen from the position of Secretary/Treasurer, and would follow as the organization’s first Black president. It was important for me to directly expose the board, and the membership, to diversity through the significant contributions of Dr. Mayo and Charles Harrison. I successfully campaigned for Dr. Noel Mayo to be Educator of the Year where he received a record number of letters from students - now leaders in the profession - in absolute support. And I collaborated with others in support of Charles Harrison to receive a Personal Recognition Award for his life's work, also highly supported. They both received their awards on the same stage and the same night at the International Design Conference to a large audience of design practitioners, educators, family, and friends. It was a proud acknowledgment of high achievement through diversity, even if only for the moment.

In 2007, the following year, Dr. Mayo, Harrison, and I had the opportunity to celebrate together as part of the “Black Creativity 2007: Designs for Life'' at the Museum of Science and Industry. This event was described as an “interactive exhibit focused on contemporary African American industrial designers for the first time, presenting the process and the people behind the cell phones, gym shoes, backpacks, light switches, and other everyday products.” Each of us was featured, along with an incredible list of other Black industrial designers, many learning about and meeting each other for the first time and representing many segments of professional and education practice.

As we celebrate this Black History Month, and I reflect on my fortuitous connections to Dr. Mayo, Horton, and Harrison, three Black industrial design pioneers and mentors that have shaped or inspired my career and served the profession in different ways, I wonder what could have happened if they had met earlier in their careers. In the recently released film, “One Night in Miami,” famed civil rights icons gathered in the same space for 24 hours, reflecting on their respective industries, societal issues, and speculating on tangible solutions to the nation’s most pressing problems. What if Dr. Mayo, Horton, and Harrison had that opportunity? Would they have been the early sages that compared profession and racial experiences, debated the path forward for exposing Black youth to industrial design, identified ways to support Black industrial designers, or found ways to work together? Today, as the saying goes, “the more things change, the more they stay the same.” While there are more Black industrial designers, and these recurring questions are being discussed, measurable progress against the same old struggles is hard to identify. The need to use the now pervasive communication tools available to connect more deeply to the Black industrial design experience, bring history and stories forward, and engage allies towards advancing the profession and its diverse potential, which is too often overlooked or untapped, is critical. This piece intends to be one contribution.

About the Author

Interim Head & Professor, School of Design